We received our Netatmo Home Weather Station earlier this week (a full review will be posted next week), and I realised that I needed to brush up on some basic geography and meteorology. Understanding the weather should help me use our new kit to forecast the weather more accurately specifically for where we live.

So I hit the books and I’m going to share my condensed findings and thoughts in this post for those of you that are interested.

Our new weather station will monitor and record temperature, humidity, pressure, wind speed and strength, as well rainfall. Having access to the data is one thing; understanding and using it effectively is a whole new ballgame.

As we move towards sustainability as a household, the weather will play an increasingly important role in our journey. The general weather forecasts on TV aren’t particularly accurate for us, because the valley that we’re situated in has its own microclimate, and the interaction of the atmosphere with variations in our topography and vegetation means that the weather varies significantly from what even happens a few miles down the road in our local town.

Having our own weather records will hopefully become an invaluable resource to producing our own weather forecasts. It is only by knowing what ‘normal’ weather is and what constitutes an extreme event in our small part of the world that will help us make our own meaningful forecasts.

With the Netatmo weather station we will hopefully start to get a feel for whether TV or internet forecasts over- or underestimate the temperature and rainfall for our location, and whether the wind speeds and directions in the forecasts match up to what we actually observe.

We can then try to explain these differences by looking at the local effects that might be causing the discrepancies.

By having our own records we’ll be able to build a picture of the typical weather conditions for our rural property, and we’re fully aware this may take a few years. This will hopefully enable us to take TV and internet weather forecasts and apply simple assumptions to them knowing, for example, that we’re generally 1C warmer than forecast or that wind speeds from a certain direction are slower.

Armed with my new knowledge and local weather data, I’m hoping that I’ll be able to produce our own weather forecasts that will be highly accurate.

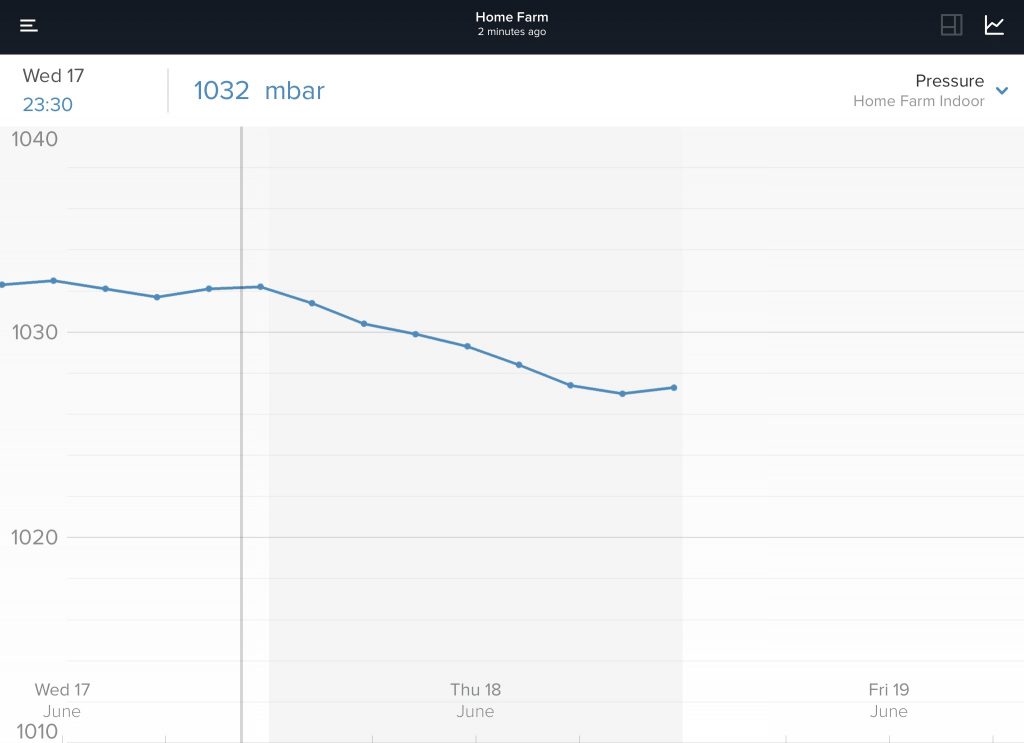

Pressure

I remember from high school geography that areas of low atmospheric pressure are associated with bad weather and areas of high pressure are generally associated with good (dry, cloud-free) weather.

Atmospheric pressure, by definition, is “the weight of the column of air above a particular point in the Earth’s atmosphere.”

When measuring pressure, we’re focusing on a point on the surface of the planet, and the pressure is the weight of the whole atmosphere above that point, from the surface right up to the top of the atmosphere.

Again, from high school geography I remember that as we go up through the atmosphere the pressure decreases because there is less atmosphere above us exerting downward pressure. At the very top of the atmosphere, the pressure will be zero.

By recognizing and interpreting the shift from high to low or low to high pressure will be critical for our burgeoning forecasting skills. We’ll dedicate an entire post to this in weeks to come, as this is paramount to understanding the weather

Why does the wind blow?

The answer lies in differences in atmospheric pressure across the surface of the planet. If there is less air in a particular column of the atmosphere than in a neighbouring one, air will flow from the column with the greater amount of air (higher pressure) towards the column with less air (lower pressure) to even out the imbalance. The difference in air pressure acts as a force, pushing air from high pressure towards low pressure.

Winds will therefore blow from areas of higher atmospheric pressure towards areas of lower atmospheric pressure. This is why pressure maps are so important on TV forecasts.

Local influences are key to understanding the weather

By analyzing our data and taking our local geography into account I’m hoping that we can start to use our knowledge to add detail to a general weather forecast which doesn’t fully factor in localized effects. Knowledge of local geography is very important in the forecast process.

The main considerations for us is our height above sea level and the impact nearby hills will have on our weather.

What causes thunder?

We’ve had a lot of thunderstorms in recent weeks. So what are they? Thunderstorms develop as a result of rapidly ascending air that carry heat and moisture from the ground into the atmosphere. This leads to the formation of large cumulonimbus clouds.

These rapid updraughts result in a separation of electric charge within the cloud, with a positive charge being concentrated near the top of the cloud, and a negative charge building up towards the bottom.

The ground beneath the cloud develops a positive charge, and if the charge difference between the cloud and the ground becomes large enough (something like one million volts per metre), the natural insulation of the air will break down leading to an electrical discharge between cloud and ground, which is visible as a bolt of lightning.

Thunder is the result of the air through which the lightning bolt passes heating up to thousands of degrees and expanding rapidly, creating a shockwave that propagates away from the lightning bolt.

The booming thunderclap travels at the speed of sound (330 metres per second); we see the lightning immediately. So if the thunder is heard six seconds after the lightning is seen, the storm will be about 1980 (two kilometers) away.

What causes snow?

There’s something calming and peaceful when it snows, but there is nothing overly special about the conditions needed for snow to fall.

Much of the rain that falls in the UK has started off within the clouds as ice particles. The key to whether these frozen particles fall to the ground as snow or melt on the way down leading to rain is the temperature of the lowest part of the atmosphere.

If the temperature of the lowest few kilometres of the atmosphere is well above freezing then snow falling through this layer will turn to rain well before it reaches the ground. If this lowest section of the atmosphere is all below freezing then any precipitation will fall as snow.

Forecasting difficulties arise when the lowest part of the atmosphere is just above freezing, giving the possibility that the snow may or may not be quite melted before it reaches the ground.